Immunotherapy

Metabolic Fitness as a Limiting Factor in CAR-NK Therapy

CAR-based cell therapy is a fundamentally different way of treating cancer. Instead of using broadly toxic drugs like chemotherapy, these therapies engineer a patient’s own immune cells to more precisely recognize and kill cancer cells. The most established version of this approach uses T cells (CAR-T), but over the past decade, researchers have increasingly turned their attention to natural killer cells, giving rise to CAR-NK therapies.

Despite promising results, many patients who initially respond to CAR-based therapies eventually relapse. For CAR-NK therapies in particular, it has remained unclear why tumors come back. A common explanation is antigen loss: that tumors adapt by changing or eliminating the targets immune cells are trained to recognize. In this paper, however, the authors argue that resistance is not primarily due to a strong tumor. Instead, they propose that CAR-NK failure arises from the immune cells themselves gradually losing fitness over time. By combining gene expression profiling, metabolic analyses, and in vivo models, they reframe CAR-NK resistance as a slow loss of energy rather than a sudden loss of target.

The Problem

Despite the clinical success of cell therapies, many patients who achieve remission eventually relapse. In the CAR-T field, this problem has been studied extensively, with tumor resistance often attributed to tumor-intrinsic mechanisms such as antigen loss, lineage switching, or chronic T-cell dysfunction.

CAR-NK therapies are slightly different. They are increasingly viewed as safer and more economically scalable alternatives to CAR-T, yet the reasons they lose efficacy remain poorly defined. It is still unclear whether relapse is driven by tumors adapting to evade killing or by the NK cells themselves becoming functionally compromised over time.

This paper aims to close that gap by asking a simple but important question: when CAR-NK cells stop doing their job, is the tumor winning, or are the immune cells getting tired, and if so, how?

Background Science

Like all immune cells, NK cells spend most of their life in a kind of patrol mode—circulating and waiting until they detect something foreign or abnormal. Once that happens, they switch into attack mode. Biologically, this means rapidly increasing their activity: boosting metabolism, producing cytotoxic molecules and cytokines, and sometimes proliferating, all in service of killing the target.

But immune cells can’t stay activated forever. Activation, much like intense exercise in humans, comes with a significant energetic cost. If metabolism can’t keep up with demand, NK cells begin to lose functional capacity and drift into an exhausted state.

Interleukin-15 (IL-15) plays a central role in NK cell biology. It supports NK cell survival, proliferation, and mitochondrial fitness, in part by enhancing glucose uptake and oxidative metabolism. While most people are familiar with the importance of IL-2 for immune cell function, IL-15 is often overlooked in cell culture and engineering strategies. Previous studies have shown that CAR-NK cells engineered to express IL-15 kill cancer cells more effectively, but until now this effect has largely been observed as a phenomenon rather than explained mechanistically.

At the same time, tumors are metabolically aggressive environments. Cancer cells often monopolize access to glucose, lipids, and oxygen, forcing immune cells to compete for limited resources. In that context, it’s reasonable to suspect that sustaining long-term dominance over a tumor may be less about recognition alone and more about whether NK cells can keep up metabolically.

What They Did

To test whether CAR-NK failure is driven by loss of immune cell fitness rather than tumor escape alone, the authors designed a study that combines transcriptional profiling, functional metabolic assays, and longitudinal in vivo tracking.

They focused on a CAR-NK product targeting CD19, a hallmark of B cells, used for B-cell cancers. This construct also co-expresses IL-15, allowing the NK cells to secrete and respond to their own IL-15 in a positive feedback loop that supports sustained metabolic activity. The authors refer to this product as CAR19/IL-15 and compare it against two controls: non-transduced NK cells (NT-NK) and a CD19-only CAR-NK product (CAR19), the current treatment standard.

To start, the authors used RNA sequencing and UMAP clustering (essentially high-dimensional ways of understanding what the cells are programmed to do) to compare NT-NK, CAR19, and CAR19/IL-15 cells. These analyses showed that CAR19/IL-15 cells occupy a less hyperactivated, more metabolically fit state. Functionally, this was supported by higher ECAR (extracellular acidification rate), a proxy for glycolytic capacity. By pairing transcriptional signatures with metabolic assays, the authors could link differences in gene expression to real energetic advantages.

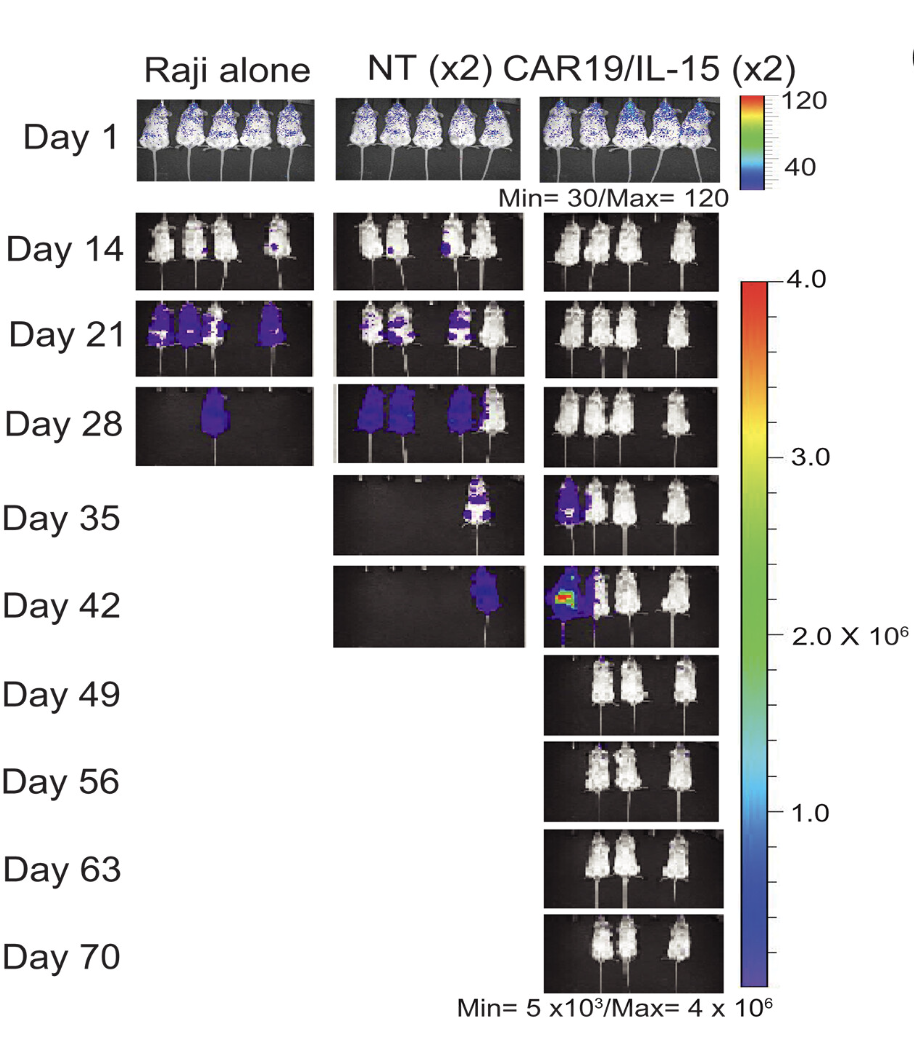

They then moved into mouse tumor models to examine persistence and resistance in a more physiological context. Mice were infused with each of the three NK cell products, and cells were harvested at defined time points over several weeks. This longitudinal setup allowed the authors to track NK cell expansion and decline, changes in gene and metabolic signatures, and whether exhaustion emerged before tumor relapse. In these experiments, mice treated with CAR19 cells succumbed around day 14, while those treated with CAR19/IL-15 survived until roughly day 35.

Over time, NK cells shifted from an initially activated state toward an exhausted one. Meanwhile, the tumor population evolved in parallel: more sensitive cancer cells were eliminated early, while more resistant subpopulations persisted. Once NK cells began to exhaust, these resistant tumor cells expanded. A key finding here is that the “resistant” tumor state was more metabolically active than the sensitive one. CAR19/IL-15 cells were still eventually exhausted, but their decline was significantly delayed compared to CAR19 cells.

Finally, recognizing that CAR19/IL-15 cells became exhausted around day 21 and largely disappeared by day 35, the authors tested a simple but clever idea: what if a second dose of CAR-NK cells were infused just as the first wave began to fail? To track the contribution of each infusion, the two doses were taken from different donors with distinct HLA markers, allowing them to be followed independently. This approach made it possible to directly assess whether renewed tumor control came from the original cells or from a fresh, metabolically fitter replacement, and the results were strikingly effective.

What's New?

This paper provides one of the first clear mechanistic explanations for why IL-15–based CAR-NK cells consistently outperform standard CAR-NK therapies. The authors generate a lot of data, but the main takeaways can be boiled down to a few key points:

- Engineering CAR-NK cells to express IL-15 confers a real metabolic advantage.

- CAR19/IL-15 cells persist longer in mice before becoming exhausted.

- As NK cells begin to lose fitness, tumors shift toward a more metabolically active, resistant state.

- Delivering CAR-NK cells in two doses, spaced two weeks apart, performs significantly better than a single infusion.

- There is a tight link between the loss of NK cell metabolic fitness and the timing of tumor regrowth.

Taken together, these findings argue that tumor resistance is not simply a case of the tumor becoming “better” at evasion. Instead, tumor outgrowth appears to be a downstream consequence of immune cells running out of metabolic capacity. The real novelty of this paper lies in shifting attention toward metabolism as a primary determinant of CAR-NK durability and long-term efficacy.

My Interpretation

CAR-NK therapy is a genuinely clever idea, but optimizing it is extremely challenging. There are countless ways researchers are trying to make these cells better cancer killers. Some groups use CRISPR to knock out genes involved in exhaustion, while others focus on tweaking CAR signaling domains to improve downstream activation and persistence.

What has stood out to me as relatively underexplored, though, is direct manipulation of immune cell metabolism. The Warburg effect was described nearly a century ago, so we’ve long known that cancer cells are metabolically dominant. While metabolism isn’t the only reason tumors evade immune attack, I think it plays a major role in driving immune cell exhaustion and eventual failure. At the end of the day, tumor relapse often looks less like immune cells “giving up” and more like them simply running out of fuel while cancer cells hoard the available nutrients.

That’s why I find this paper particularly compelling. The authors don’t just show that IL-15–engineered CAR-NK cells work better. They propose a clear metabolic rationale for why that improvement exists. Rather than treating metabolism as a secondary readout, they place it at the center of CAR-NK durability.

I think this work has real impact potential for the field. It should encourage more researchers to treat metabolism as a design parameter, not an afterthought, when engineering cell therapies. Overall, I see this study as an important conceptual shift rather than a finished solution: it tells us where to look when CAR-NK therapies fail, even if it doesn’t yet tell us exactly how to prevent that failure.

What I'd Do Next

To me, the most important limitation of this paper is that all of the experiments were performed using liquid tumor cell lines, specifically Raji and K562. While liquid cancers are metabolically active, they are far less competitive than solid tumors. This is likely one reason CAR-NK therapies have been most successful in hematologic malignancies, and it’s encouraging to see that IL-15 engineering further improves outcomes in this context.

The real test, though, will be extending this framework to solid tumors, where cell therapies have historically struggled. Although both liquid and solid tumors compete aggressively for glucose and lipids, solid tumors add another layer of difficulty by creating profoundly hypoxic microenvironments. By efficiently consuming oxygen, they generate hypoxic cores that place even greater metabolic stress on infiltrating immune cells. IL-15 clearly helps CAR-NK cells maintain fitness along some metabolic axes, but I’d be curious to see whether additional engineering strategies could account for other features of the solid tumor microenvironment, particularly hypoxia. I’d also want to explore how staggered dosing strategies could be optimized. This paper shows that a second infusion can restore tumor control, but it leaves open important questions: when is the optimal time to re-dose, and could early metabolic readouts predict when replacement is needed? With the right biomarkers, CAR-NK therapy could become a feedback-driven system rather than a one-shot intervention.

Something I Learned

One unexpected takeaway from this paper was how powerful UMAP-based clustering can be as a storytelling tool when it’s used well. Instead of visualizing heterogeneity for its own sake, the authors used dimensionality reduction to make a clear argument, showing NK cells transitioning from highly active, metabolically demanding states toward more exhausted ones as therapy progressed. Even though it was a bit hard to follow at first, the overall trajectory ended up feeling far more intuitive than scrolling through raw gene lists ever does.

More broadly, this paper reinforced something that’s easy to forget when staring at dense figures: scientific papers aren’t just collections of experiments, they’re narratives. The authors made deliberate choices about which data to highlight and how to order their results to support a central claim. Writing about this study forced me to practice the same skill: distilling a long, complex paper into a short, coherent story, which feels like good training for communicating science more clearly later in my career.

My Favorite Figure

References

- Li, L., Mohanty, V., Dou, J., Huang, Y., Banerjee, P. P., Miao, Q., Lohr, J. G., Vijaykumar, T., et al. Loss of metabolic fitness drives tumor resistance after CAR-NK cell therapy and can be overcome by cytokine engineering. Science Advances 9(30):eadd6997 (2023).